Book review by Graeme Kemp:

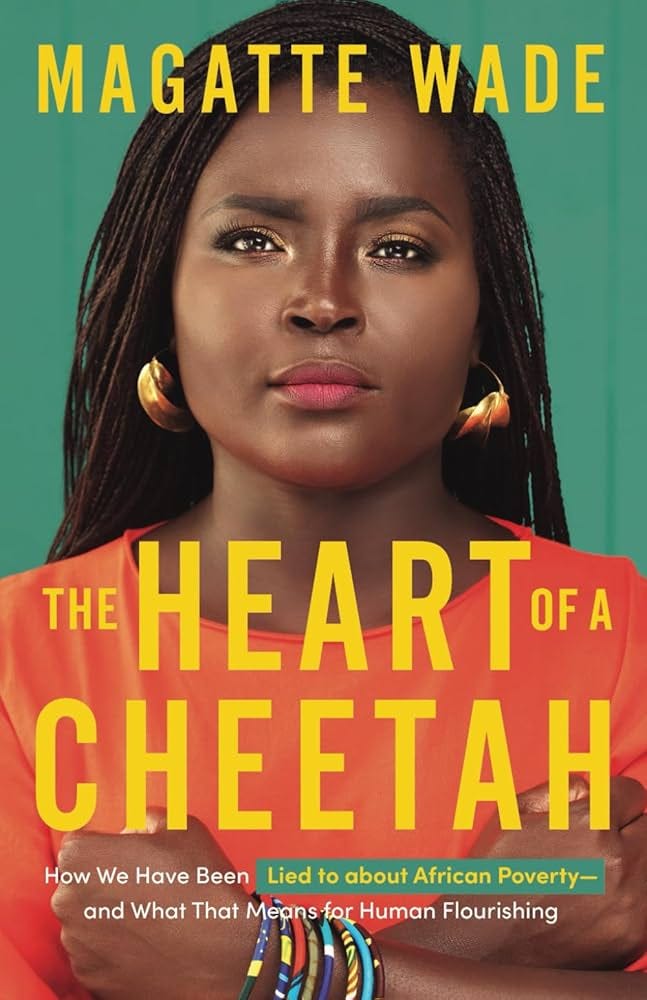

The Heart of a Cheetah: how we have been lied to about African poverty – and what that means for human flourishing’ by Magatte Wade; Cheetah Press; 2023; USA; 267 pages.

Few books these days can have such an emotional impact as The Heart of a Cheetah by entrepreneur Magatte Wade, originally from Senegal. It reads more like a thriller in parts as she vividly describes her physical as well as intellectual journeys – and the challenges she overcame. Flying unashamedly in the face of many contemporary political and economic perceptions of Africa, Wade makes bold claims for what she says is the genuine solution to poverty and lack of progress is in that continent: truly free markets and a rolling back of state socialism.

If Africans remain stuck in a victimhood narrative about why poverty persists, then few things will change for the better, she argues. It’s time for a new generation of Africans to seize hold of a better future and build it themselves:

“There is hope for Africa, and it rests with the Cheetah Generation.” (Page 23).

So, who is the Cheetah generation?

Magatte Wade sees them as a new emerging class of young graduates and professional people in Africa. They are fresh and keen to change things - and they look at Africa in a new, positive way. They are no longer held back by their relationship to colonialism, the slave trade or even their post-colonial leaders following independence, such as Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta, Kenneth Kaunda or Julius Nyerere:

They do not have the stomach for colonial-era politics. In fact, they were not even born in that era. As such, they do not make Excuses for or seek to explain away government failures in terms of colonialism and the slave trade. Unencumbered by the old shibboleths of colonialism, imperialism, and other external adversities, they can analyze issues with remarkable clarity and objectivity. (Page 24).

The main reason Africans are poor, claims Wade, is that they have not been allowed to develop the companies that would lift them out of poverty by creating wealth. Layers of government bureaucracy and restrictive laws prevent this from happening. Only when the economic shackles of over-regulation are thrown off, will Africans earn the respect of the rest of the world. Economic success will create a new narrative around what it means to be African. This optimism radiates throughout ‘The Heart of a Cheetah’ and lights up every page. Ordinary Africans are honest and industrious, argues Wade – they just need the opportunity to build their own dynamic future.

And if African nations keep relying on foreign aid or ‘do-gooders’ from outside the continent, she says, few things will change. Africa needs private investment - not charity. Outside interventions often fail to solve problems in the long term.

Magatte Wade explains how difficult it is to do business in countries like Senegal, a place where she says only about 5% of companies operate legally – the other 95% illegally. Yet if companies in that 95% get too large, the government will start to take too much of an interest in them; government bureaucracy and over-regulation will then dampen any further growth, she argues. This will stifle the “throbbing energy, power and rhythm of an African entrepreneur.” (Page 26).

To an outsider, Africa’s problems often seem to require more regulation and new laws. However according to Wade, that kind of intervention will not work in reducing poverty or helping Africans succeed. Africa’s business owners are in chains - shackled by a poor business environment.

Companies in Senegal do also have employee protection regulations, but these are often flawed: they only protect workers on paper – the reality is that employees can still be treated very badly.

In the past, African countries were indeed prosperous – and could be so again, says Wade. All too often those in the West see the continent and its diverse peoples as defined solely by civil wars, genocide, and starvation (the ‘flies in their eyes’ charity images). The only ‘positive’ alternative to those stereotypes is the representation of Africa as a kind of vast Disneyland – think of ‘The Lion King’ or ‘Madagascar’, for instance. Often, those in the West do not even think of Africa at all…. Africans need to change those misplaced representations, Wade forcefully argues.

However, she ironically adds, many Africans also have stereotypes of white people in the West! All people have their biases, it seems.

A large part of ‘The Heart of a Cheetah’ is therefore an account of how Magatte Wade reached the conclusions she has. She was born in Africa but moved to countries outside the continent like Germany, France and the USA developing her career. Wade’s book focuses on how she gained her valuable business knowledge and developed her own businesses – it’s an often a gripping story that she tells of overcoming adversity and developing a resilient mind-set.

When planning to move to Europe, her grandmother offers her some advice about the people she will encounter:

Even if most will not look like you and will have a different skin color, they are still humans, and you are a human being. The different language you will find them speaking is still a language spoken by humans, and you are a human being.” (Page 62).

This forms part of her outlook as she moves from country to country, absorbing information and looking for solutions to business problems. Her mantra is: criticise by being creative. Being aware of one’s own agency is vital – as is an open mind and an open heart, Wade adds. And nobody could doubt she is hard-working. Mindful and respectful of Africa’s rich history and cultures, Magatte Wade remains outward looking and interested in the people and places she meets everywhere. It is only the well-meaning charity sector activists and ‘anti-capitalists’ she is less keen on. And she isn’t a fan of cancel culture – it holds back honest discussions and debate. She recognises that racism and discrimination can still exist, even if she isn’t a fan of Ibram X Kendi and his critical race theories.

Being aware of one’s own agency is vital – as is an open mind and an open heart, Wade adds.

In the USA she was able to work with now household names like Google and Netflix, before later returning to Senegal. Wade clearly lives an active life, even if it included overcoming personal tragedy including the loss of her first husband. Heart of a Cheetah contains some very moving and personal stories.

So, what solutions does Magette Wade propose to let Africa succeed and unleash the Cheetah generation?

Principally, she advocates what she describes as Startup Cities, economic enterprise zones with lower taxes - and free of unnecessary regulation. These are sometimes described as Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Cutting-edge education and an effective legal system would also help these Startup Cities succeed, she claims. They would attract the brightest and best entrepreneurs. African countries would then supply the rest of the world with world-class goods and services. Networking and supporting African businesses as either consumers or investors, are also vital.

Wade ends her fascinating book with the following rallying cry:

Because when Africa finally achieves prosperity, it will unlock a future so bright we can hardly imagine it. (page 256).

The Heart of a Cheetah is a remarkable book by a remarkable woman. It is refreshing to read such a positive account of what she believes is possible. I’m not sure I always fully agree with the small-state, free-trade, ‘hire-and-fire’ and low tax beliefs she advocates, but her enthusiasm and humanity are undeniably inspiring.

Graeme Kemp is a former teacher and civil servant who currently lives in the Midlands. He is an English and Cultural Studies graduate of several universities in England and Scotland. He has also contributed book reviews to the Don't Divide Us website and 'Bournbrook' Magazine.

🚨Event Announcement

The countdown to the Battle of Ideas festival has begun!

On Saturday October 19, and Sunday October 20, Church House in Westminster will become the epicentre of thought-provoking discussions on the most pressing issues of our time.

The Equiano Project is proud to be hosting a panel discussion on Islam, Islamism, and Islamophobia. In an era where the line between legitimate critique and bigotry often blurs, this conversation couldn’t be more timely. How do we effectively combat anti-Muslim hatred while preserving the crucial right to discuss and critique all religions openly and fairly?

Our distinguished panel will tackle this vital question and more, examining key events such as the Salman Rushdie affair and other recent controversies to shed light on how to approach discussions about Islam and Islamism critically in the UK.

Join the Battle of Ideas festival for an unmissable weekend of debate and discussion on the most critical political, economic, scientific, and cultural issues of our time.

Find out more and book your tickets, here or follow the link below:

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/battle-of-ideas-festival-2024-tickets-807629249827?

This looks a most interesting read and I'm sure I would heartily agree with most of the points Magatte Wade makes. Like many people of my generation, I was sensitized to the problems of development in Africa by the awful famine in Ethiopia in 1984. I responded by becoming a VSO volunteer - a role that actually took me to an agricultural project in Indonesia, rather than anywhere in Africa - but I remained involved in 'development' for several decades, to the extent my 'day job' allowed. In particular, I supported the work of a small NGO working in Tanzania.

One observation I would make is that back in the 80s (and ever since), all the big UK aid agencies were staffed by people who had a left-wing perspective on aid and development. Their energy was devoted to highlighting the injustice of the international economic system and campaigning for more government aid. Yet my experience in Indonesia had shown me that successful and sustainable development comes from the drive and energy of local people and that, if grant money for capital investment was needed in the early stages, there seemed to be quite a lot of money around. Even then I felt that campaigning for a percentage of GDP to be spent on aid was all back to front. Great for the aid agencies, but not much good for development.

Later, having become older and more cynical, I have come to the conclusion that aid agencies are actually doing more harm than good. Aid has become very big business and too many careers and lavish lifestyles are fueled by aid - and too many communities and local economies are disrupted by aid. It was great to see the President of Ghana, Nana Akufo-Addo delivering a lecture to President Macron on the need to break away from dependence on aid. Here's the link: https://youtu.be/aPEeiFBUwM4?si=92biB70haJW586sh