- Written by Ildi Tilmann

When you talk to people privately in art- and entertainment circles in the United States, many of them will tell you that the industry has been engulfed in ideology and that, as a consequence, the creative professions are in crisis. Financial support goes to politically well-aligned artistic projects, or to artists whose identity label will positively reflect on the activist goals of the grant maker. Classical training, fine art and artistic competence are frequently sidelined to benefit superficial projects that recycle trendy ideas, or to ones that support social engineering goals.

Most art grant-makers in New York and the wider East-Coast ask applicants to declare their ’race’, ’gender identity’, ’housing status’, ’disability status’, ’sexual identity’ on the grant proposal. While one can ’prefer not to disclose’, it is well understood that disclosing the right status or ’identity’ is, in fact, a factor that will be taken into consideration when granting support to a project.

Grant-makers rarely create grants for open-theme, multidisciplinary or intellectually complex ideas. Artists who want to create across disciplines or who want to explore timeless human themes rather than talk about specific political struggles of the moment, will not fit the mould of prescribed funding-categories and end up having little chance to even apply for grant money. The past decade has seen a more and more distorted creative space, where the works of art the audience sees are not representative of the real concerns or desires of a wide range of artists – they are representative of what the funding agencies would like to see created.

Add to all this the effects of fast-media, of AI-‘enhanced’ communication and of a hyper consumerist social context where individuality is confused with personal branding, and you end up with a situation where authentic thought and creation have less and less space to exist.

In 2011, the famous jazz musician and trumpet player Wynton Marsalis observed that, we are living through a morass of social and cultural underachievement, (...) an era of hysterical nowness, when our fine art has floated away”. The situation in the past fourteen years has not improved. If anything, it only became worse.

It is in this cultural context that I would like to introduce my ongoing project, Captured Landscapes: Cuba - New York, which I am working on in collaboration with composer and jazz pianist, Elio Villafranca.

The idea for this project came to me on a rainy evening in December of 2023, in a cab, near Times Square in New York City. Protected from the downpour but slowed to a standstill by traffic, I had nothing better to do than watch the huge, flashing billboards that light up– and overshadow - that area of the city.

Then my attention shifted to the tourists on the streets, flooding in and out of the hotels, and to the food delivery workers on bicycles, braving the rain, busy trying to make a living.

I took a few random photographs through the water-streaked car window, and the next morning I took some photos from the 15th floor of a building facing the square. When I looked over the photographs later that day, their dystopian message was impossible to miss. There were two dimensions of life reflected on pictures: the level of the streets with people, and the level of flashing screens, advertising and news headlines. It was a space where real life was in the shadows while curated, socially engineered life was front and centre.

In the space the photographs showed, digital messaging and commercial propaganda overshadowed aspects of life I considered human.

While the area around Times Square clearly represents only a small part of New York City, it is a striking visual metaphor for the world we live in. A world of advertising, social media posts and bottomless, simplistic news feeds. A world where slogans rule, where authenticity and complex thought are drowned out, if not outright punished.

Slogan-shaped realities are well-known to us who grew up in Eastern Europe at some point in the twentieth century. We know how such worlds are born and where they invariably lead to. We know it less through experience with commercial advertising, but from our history of authoritarian regimes, both from the left and the right of politics. We know it through our experience with forcibly politicized social and cultural spaces where ideology overrode liberal, intellectually diverse education, and it flattened creativity and the arts.

The photos I took on Times Square that day made me wonder about the effects of propaganda on our consciousness - be it for commercial or for political goals. Where does information end and propaganda begin? Does art necessarily end where activism starts? How can one not lose one’s way along this hazy path?

In my mind, I recalled forms of refuge we took against the slogan-based external reality that surrounded us. I recalled our sounds and silences, our images, our films, our theaters… our art. Rarely shiny, hardly ever glamorous, almost always personal. I remembered the importance of the private, the intimate, the individual. And I decided that the time has come to create a project. About the past and the present, about the importance of art in education, and about art as a refuge from the effects of the ideological.

Always attracted by multimedia formats and comparative contexts, I landed on the idea of a series of photographs and personal interviews in Cuba and in New York, accompanied by music composed to these photographic and interview archives. I knew that the best musician to work with me on such a project would be someone whose music is deep, creative and visionary, one that possesses a strong narrative character. I knew a person like that from previous work: Elio Villafranca. I called him, described the idea to him, and I asked if he would be interested in working with me. When he said yes, Captured Landscapes: Cuba – New York was born.

Our artistic and educational approach to the project

We will merge artistic-documentary photography, jazz/Latin jazz music to reflect on human life and on the effect of ideology, propaganda and slogan-driven communication in two contexts: Cuba and New York. Our work will offer comparative, multimedia material for both an artistic experience and for education. Our project motto is a quote from Andrei Tarkovsky, a Russian filmmaker who lived and created during the Soviet era: "How can we really get to know each other? By abolishing the frontiers."

With our work will show that by abolishing the human-drawn frontiers not only between musical genres and artistic disciplines (photography and music), but also between education and art, we can connect seemingly different human histories, highlight their ebb and flow, and understand how they interact to strengthen each other.

Our goal, and what we will create

Our primary goal is to inspire the audience to ask themselves: What is true, and what is it that is being marketed to us? How shall we know the difference if our physical and mental landscapes are captured by clichés and slogans?

The completed project will include:

two extensive archives of Ildi’s photographs guided by the project goals – one archive from Cuba and one from New York

a small collection of photographs from historical archives in Cuba and Eastern Europe that connect to the project theme

written stories to accompany the photographs.

Elio will compose 60 minutes of jazz and Latin-jazz music for a septet, inspired by the project photographs and stories. The Cuban-inspired part of the music will take the audience back to the era when the revolution was still young, and it will trace its continuity to the present. The music for NY material will be inspired by American and other local ethnic influences (immigrant cultural influence).

Elio will produce an album-length recording.

Once completed, the full photographic and musical material will be made available online. The material we create will be suitable for multimedia exhibition-formats at physical venues, and for full-evening, live jazz performances where the project photographs can be digitally displayed.

Our work will aim to forge a path to move beyond the parochial thinking patterns of contemporary North America obsessed with ‘identities’ rooted in race and gender. It will encourage viewers and listeners to recognise shared experiences within the flow of human history, and to consider that knowing and accepting each other is not simply based on ‘celebrating difference’, but on recognising that history and human stories have patterns, they are frequently repetitive, and they are hardly ever black and white.

I believe that human stories are like mirrors. If you line them up facing only you, with their sides touching each other, you end up seeing yourself only in the one mirror right in front of your eyes. But if you line them up facing each other with you standing in the middle, you will see myriad reflections of you on all sides.

Ildi Tillmann is an author and photographer. Her project neither conforms to establishment-supported art categories nor promotes a collectivist, social identity-based worldview. To help make Captured Landscapes a reality, please consider making a donation through this Indiegogo page. You can also connect with her on social media: @tillmannildi or @ildikotillmannphotography.

Website: ildikotillmann.com.

Havana photo gallery: https://ildikotillmannphotography.pixieset.com/cuba/

Elio Villafranca YouTube page: https://www.youtube.com/@ElioVillafranca

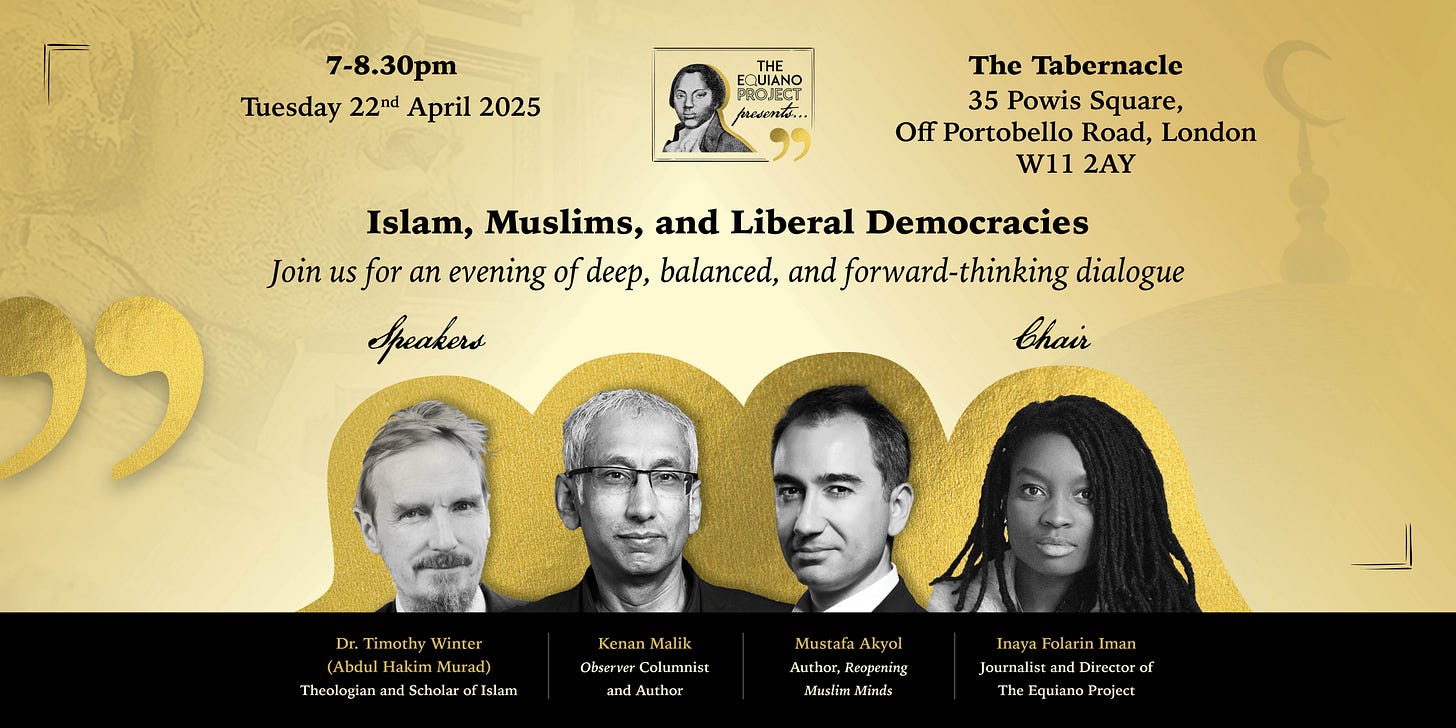

UPCOMING EVENT THIS APRIL

Islam, Muslims and Liberal Democracies

An evening to discuss Islam’s place in Western secular societies

Click here to grab your tickets, or follow the link below.

(Paid subscribers are eligible for a discount—click here to redeem yours!)

I will be LIVE with Ildi Tillmann tomorrow at 8pm GMT on Substack (4pm ET)

In this exclusive livestream, we will examine the rise of ideological narratives in the art world, the effects of identity politics on creative freedom, and the ongoing challenge of maintaining authenticity in a socially-conscious, politically-correct age.

See you there!

When I was younger artists could not get a grant for anything as far as I know. They needed to produce art that people would buy which is why we never saw banana’s and unmade beds in art galleries.