A Dangerous Shift in the Name of Equity

Why race should never factor into sentencing decisions

The principle of blind justice is one of the most fundamental pillars of any fair legal system. Liberal societies that uphold this ideal may not always get it right, but the commitment to equality before the law remains a defining characteristic. Yet, in an era where identity politics increasingly permeates every facet of modern society, even the judicial system is now not immune to the push for differential treatment based on race.

Pre-sentence reports (PSRs) have long played a key role in sentencing decisions, particularly in cases where additional context about the offender’s background is needed to help courts determine an appropriate sentence. Typically prepared by probation officers or other legal professionals, these reports provide insight into an individual’s background and criminal history. Sentencing recommendations have generally avoided considering race or ethnicity. Legal systems that aim to prioritise fairness and neutrality tend to focus more on individual circumstances than on demographic traits.

However, new guidelines seek to change this approach. The Sentencing Council now calls for a PSR to be completed before sentencing offenders from “ethnic, cultural, or faith minorities.” This marks a significant shift, as PSRs were previously required only in specific cases, whereas they will now be “considered necessary” for individuals from these groups. While this policy is framed as a step toward fairness, it raises serious concerns about whether sentencing will be influenced by factors unrelated to the crime itself.

Policies like these assume that ethnic minorities cannot be held to the same standards of accountability as others. This belief is not only racist but also deeply patronising. Justice must be applied consistently, without regard to racial identity. Deviating from this principle not only erodes public trust in the legal system but also acts as a way to institutionalise unequal treatment under the guise of equity. It creates a system where certain individuals may be judged not only by the severity of their crime but also by the perceived disadvantages or challenges they face based on their racial or cultural background.

The argument that ethnicity should be factored into sentencing recommendations is also based on existing disparities in the criminal justice system. The progressive perspective today often embraces new forms of discrimination as a tool for balancing the scales between racial groups. However, the goal should not be to manipulate results in order to correct statistical imbalances.

If public institutions are serious about addressing disparities, they should shift the focus to cultural attitudes toward crime. For example, the “no snitch” culture in certain communities or the reluctance to co-operate with law enforcement due to a persistent, misguided lack of trust.

Shadow Justice Secretary Robert Jenrick has expressed frustration that these changes are unfair to straight, white, and Christian men, and he has a point. However, it is also a great disservice to actual victims of crime when the perpetrator’s ethnicity is taken into account, especially if it can potentially lead to a more lenient sentence.

Not long ago, a young black boy was fatally stabbed. His last words were, “I’m 15, please don’t let me die.” Victims of violent crime do not care about sentencing disparities or ideological narratives. Those who commit senseless crimes, regardless of their background, are not victims—the true victims are those harmed and the family members left to suffer. The race of the perpetrator should have no bearing on the determination of consequences, regardless of how minor its influence may be. The mere act of considering it sets a dangerous precedent, and shifts the focus away from the crime itself.

Some equality activists might argue that ethnic minorities, beyond the criminal justice system, face widespread disadvantages in life and do not benefit from the same privileges as white individuals. They may welcome these new guidelines, believing that issues like discrimination, poverty, limited access to education, and a lack of opportunities should be considered when determining punishment. However, these challenges are not unique to any one racial group; they can affect individuals of all races. If activists care about addressing disadvantage effectively, the focus should shift from race or ethnicity to socio-economic status. Policies should reflect this broader perspective, and accept that class and economic hardship are the primary drivers of disadvantage, rather than assuming non-white individuals are inherently more oppressed.

Any attempt to include race or ethnicity in sentencing decisions is a direct assault on the core principle of justice. Introducing these aspects into the process is not a genuine solution to inequality; it is a harmful distortion of the justice system that will only increase polarisation and make matters worse. Such an approach will undoubtedly establish a two-tier system, directly contradicting those who dismiss these concerns as little more than a right-wing talking point.

Ada is the Head of Content at The Equiano Project. Subscribe to The Equiano Project YouTube channel HERE.

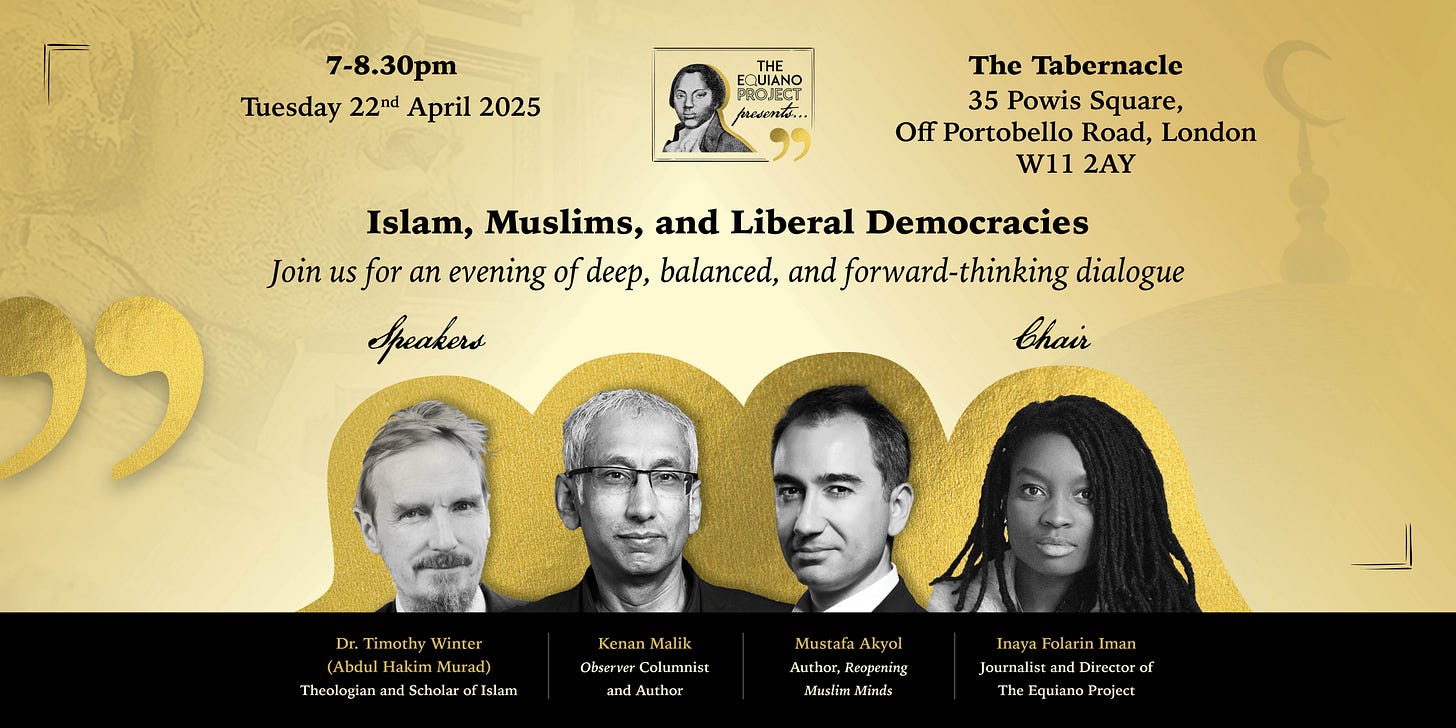

📢📢TICKETS STILL AVAILABLE

Islam, Muslims and Liberal Democracies

An evening to discuss Islam’s place in Western secular societies

Click here to grab your tickets, or follow the link below.

(Paid subscribers are eligible for a discount—click here to redeem yours!)