What I Found in Israel Was a Society Defiantly Alive

Reflections on nationhood, belonging, and shared destiny

These are the personal views of the author, and we welcome articles that disagree, even strongly, with the views expressed in this piece. As an organisation, we recognise that there can be mutually exclusive, yet equally valid, perspectives on sensitive matters, especially in the realm of foreign policy.

Before October 7th, I hardly paid attention to Israel. I saw it as a liberal democracy in a tough neighbourhood — a nation born from the ashes of the Holocaust, existing as a refuge for Jews in a world that had once turned its back on them.

Whenever the topic came up, I instinctively recoiled, not out of discomfort with Israel itself, but because of how irrational and emotionally charged the debates always became. To me, its existence wasn’t up for discussion. It simply was. Whether or not someone believed Israel had the “right to exist” felt like asking whether gravity had the right to pull things down. Israel was not the only modern nation that came to be in complex circumstances, just pick up a history book.

Of course, the periodic clashes with the Palestinians were tragic. I support peace. I wish peace could come. But the greatest minds of our time have tried and failed to bring it about. And so I came to view Israel’s actions, while often harsh, as part of the brutal realpolitik of a region where violent Islamism doesn’t just exist, it thrives.

When I heard accusations of apartheid, settler-colonialism, or even white supremacy, I rolled my eyes. These labels usually came from the same people who accuse white people with dreadlocks of being colonisers, people whose worldview has collapsed into a simplistic binary of oppressed vs. oppressor. You could call me a light-touch Zionist: vaguely supportive, but mostly detached.

That all changed on October 7th 2023.

The sheer brutality of Hamas’s attack shook me to the core. The sadism, the joy taken in killing, the targeting of civilians, children. It was evil laid bare. Nothing, absolutely nothing, could justify it.

But worse, in a way, was the global reaction. Many groups that claim to be anti-racist, anti-fascist, and champions of the oppressed leapt to excuse, minimise, or outright celebrate the horror. People tore down posters of kidnapped Israeli children with smug righteousness.

And when Israel responded, as any nation would after a massacre of its civilians, it was immediately placed under impossible moral scrutiny. It was expected to defend itself, but without force. To rescue hostages, but without causing civilian harm. To destroy a terror group embedded in schools and hospitals, but without upsetting international opinion. Take how Israel is frequently criticised for preventing aid from entering Gaza. Even setting aside that Israel disputes many of these claims, few pause to ask the obvious question: why is Israel expected to feed a territory it is actively at war with? Or why Egypt — which also borders Gaza — rarely faces scrutiny for keeping its own crossing largely closed? The outrage is selective, and the expectations are uniquely moralistic when it comes to Israel.

No other democracy, facing a comparable attack, would be held to such a standard, one that effectively demands passivity in the face of annihilation. I supported Israel’s war. What other option did it have?

But war grinds on. The aims — freeing the hostages, destroying Hamas — remained unfulfilled. The images from Gaza: rubble, injured children, wailing mothers, they started to wear on me. Accusations of collective punishment, war crimes, genocide — relentless and growing. My support waned.

I needed to see it for myself. And so I went to Israel.

I expected to find a country embittered and fragile, perhaps even paranoid or propagandist. A nation closed off, consumed by rage.

But what I found was the exact opposite.

People were open, spirited, and engaged. Not hate-filled, but resilient. Not blinkered by ideology, but full of debate and self-examination. The fear I imagined wasn’t there. Instead, there was clarity. There was purpose.

What I found in Israel changed me again.

It reaffirmed my faith in humanity, not because it’s perfect, but because it is defiantly alive. Israel, paradoxically, is everything Britain claims to want but seems afraid to be.

While the West tears itself apart in guilt, self-loathing, and cultural unravelling, Israel knows why it exists. It doesn’t apologise for itself. And that kind of national confidence is magnetic.

One of the places I visited was Kibbutz Nir Oz — one of the communities most brutally destroyed by Hamas’ sickening pogrom. A quarter of its residents were either murdered or kidnapped. The attackers disfigured what had been an idyllic, peaceful place — home to many who had spent their lives advocating for coexistence and solidarity with Palestinians. Our guide was Rita Lifshitz, the daughter of Oded Lifshitz, who was killed in captivity by Hamas. What struck me most wasn’t just the scale of the devastation, but her strength. She had every right to be bitter, to be broken. Instead, she was composed, clear-eyed, and committed to carrying on. Her resilience said more about the spirit of Israel than any flag or speech ever could.

Israeli society is messy, diverse, fractious yet full of meaning. Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Mizrahi, Beta Israel, Arab-Israelis — the diversity is real, but it’s not curated or performative. The mixing is organic, the kind that happens when a people are bound by a shared destiny. It blends East and West in a way that feels natural and lived-in, not imposed. You can taste it in the food, hear it in the music, and see it in the faces of the soldiers and schoolchildren. It’s imperfect, but authentic — and far more powerful than the checkbox multiculturalism we’ve grown used to in the West.

There’s no confusion among young Israelis. They serve, they sacrifice, they fight for their country. They wear the uniform with pride, not out of blind nationalism, but because they believe in the nation itself.

Israel is one of the rare liberal democracies that hasn’t collapsed into hyper-individualism and hyper-liberalism. It avoids so many of the traps the West seems unable to escape — the loneliness, the consumerism, the hollowed-out communities. People don’t just live next to each other, they live with each other.

Family, faith, community, these aren’t nostalgic buzzwords. They are real. Children are everywhere. Parents raise them not with fear or resignation, but joy.

Even the ultra-Orthodox in Israel, a group often criticised for insularity and religious rigidity, are not caricatured or dismissed. There’s real tension, yes. Their exemption from military service, dependence on welfare, and growing share of the population present real challenges to Israel’s social contract. Many Israelis resent that they do not serve in the IDF, even as their birth rates suggest they’ll make up a much larger portion of the population in the years to come. It’s a real source of friction. But there’s also an effort to understand them, to engage with their worldview, to debate their role in national life rather than simply write them off. They are seen, ultimately, as part of the same story.

Compare that to Britain, where the white working class is increasingly treated as a kind of embarrassing relic — reactionary, provincial, in need of re-education or quiet erasure. Rather than engage, our elites pathologise. Rather than listen, they sneer. A whole segment of society, people who once built the country, defended it, kept its cultural flame alive, is now talked about as though they’re simply just a problem.

In Israel, debate is robust, open and fierce. We also visited the Hostage and Missing Families Forum — the central organisation representing the families of those kidnapped by Hamas. There, the pain was raw. Anger, frustration, and heartbreak hung thick in the air. Nothing was sugar-coated. Families spoke freely, and there was no unified message. Some were furious with the government’s handling of the war and the negotiations. Others placed blame elsewhere. But what struck me most was how open it all was. Even in their grief, people weren’t afraid to speak with total honesty. The room wasn’t managed or choreographed — it was a space of real democratic anguish.

Meanwhile, in Britain, despite not facing an equivalent violent existential threat, the picture is bleak. Our trust in institutions is low. Our culture of victimhood saps our will. We’re afraid to name Islamist extremism, even after politicians are murdered. Our cities are neglected. Disorder grows. The streets feel less safe, our politics paralysed. Birthrates are in freefall.

We are tired. Israel is not.

I should be clear: this essay isn’t an attempt to ignore or oversimplify Israel’s challenges. The occupation is real. Palestinian suffering is real. The moral and political complexities here run deep, and they defy easy answers. This isn’t a policy paper or a defence of everything Israel has done. It’s simply a reflection from someone who went from distant observer, to shaken supporter, to something more complicated, more admiring, and more troubled. What I saw in Israel moved me. It reminded me what a nation looks like when it still believes in itself.

Israel, for all its flaws and existential threats, is something the West can’t quite understand anymore: A nation where young people serve, families grow, the past is honoured, and the future is still something to fight for.

And perhaps that’s why so many people hate it. Because, deep down, we envy it.

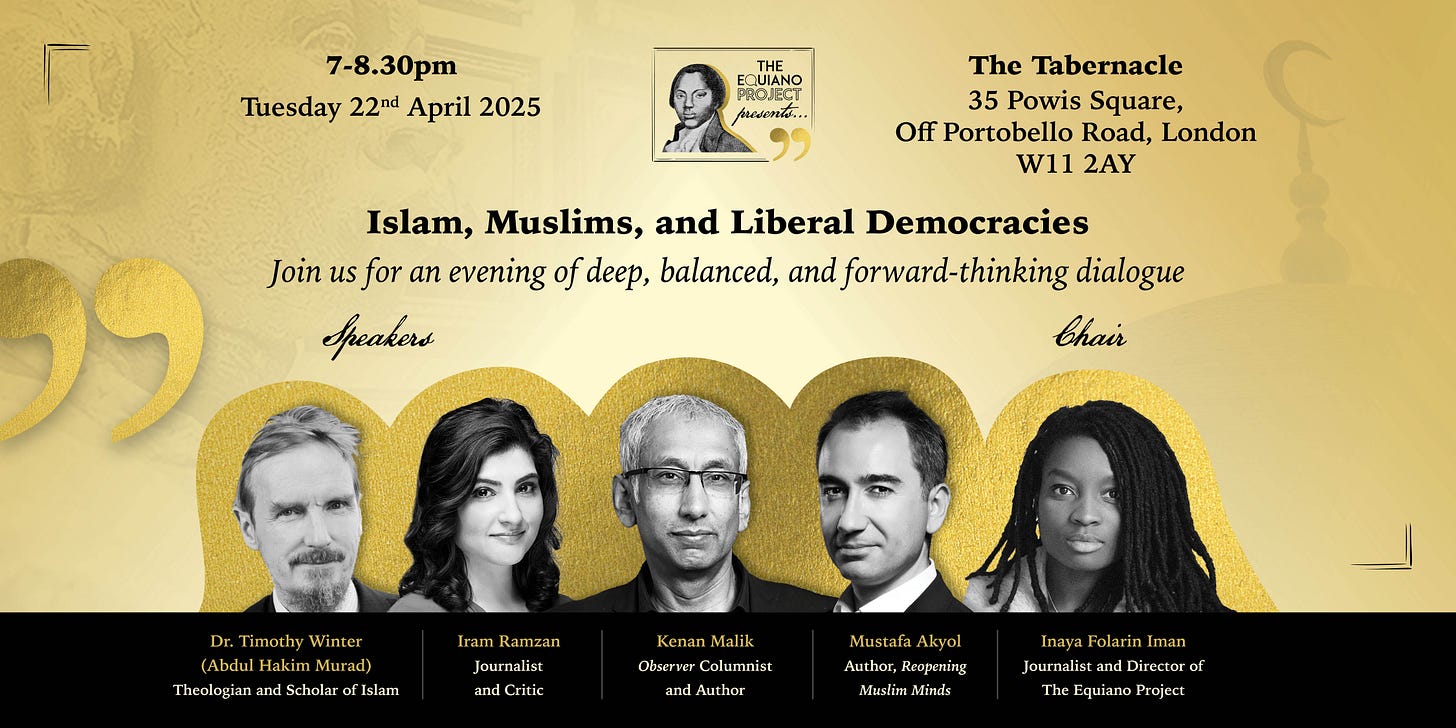

Join Equiano Project director Inaya Folarin Iman as she chairs a crucial discussion on Islam, Muslims, and Liberal Democracies.

Click here to grab your tickets, or follow the link below.

(Paid subscribers are eligible for a discount—click here to redeem yours!)

Great essay, very interesting to read a firsthand impression and comparison like this.

I loved your article, Inaya, and I'm so pleased you found the time and made the effort to go see for yourself. I spent a couple of months in Israel in '91 - working on a moshav and just taking in the country. I loved the energy, the optimism and the diversity of the place - diversity with unity though, couldn't we in Britain learn from that? There was trouble at that time, cross-border raids by Hezbollah were a weekly, sometimes daily, occurrence, but life felt free and easy and relaxed. Everybody hitch-hiked everywhere, which was no longer the case in England, it was easy to get a ride - back home we were becoming fearful and insular, Israel felt more like the free and easy 60s. If I had been Jewish, I would definitely have wanted to return to stay and help build the country. I've hated the way Israel has been propagandised against over the past three decades, and I have come to the view that the bias against Israel and the deliberate lies and misrepresentation can only be explained by deep-seated antisemitism - the oldest prejudice of them all. But I know that many people won't agree with that. Anyway, thanks again for your article - some light at a dark time.