What is the weight of an American heritage on blackness? A person’s blackness doesn’t tell much about them. Being black in the United States doesn’t identify whether one is old or young, a city dweller or a suburban denizen, a collectivist or an individual. If there are over 40 million black Americans, there are over 40 million life stories. While being black in the United States encompasses a vast array of experiences and perspectives, indigenous black Americans seem to carry a distinctive weight.

I am not the first to sense this peculiar weight.

Author Malcolm Gladwell has eloquently observed that West Indians can often identify each other due to the absence of this weight. Gladwell's insight speaks to a set of shared values, attitudes, and mindsets. Unlike black immigrants, who may approach prejudice as a hurdle to overcome, indigenous black Americans often grapple with it as a deeply ingrained challenge to their sense of self. For instance, it's uncommon to find an indigenous black American attending elite institutions like Harvard, Yale, or Stanford. Most black students in said institutions, the equivalents of Oxford and Cambridge in the United Kingdom, are not self-identified, unmixed descendants of American slavery from the 1600s, 1700s, and 1800s. Most are immigrants, offspring of immigrants, or children of black and non-black parents.

Consider this statistic: 77% of black doctors in the United States are Nigerian immigrants, yet Nigerian immigrants make up only 1.69% of the black population in America. A significant portion of these immigrants likely hail from the Igbo ethnic group. This raises the question: why do Igbo and other immigrants dominate black medicine in the U.S.?

My theory is that Nigerian immigrants, including many Igbos, arrive without the burden of racial barriers ingrained in African American upbringings. For them, excelling in fields like Organic Chemistry or pursuing a career in medicine is simply part of their destiny. There's no heavy burden of American heritage weighing them down. Whether they're Nigerian or West Indian, black immigrants tend to navigate obstacles with resilience and determination, focusing steadfastly on their life goals.

For instance, if a high school guidance counsellor attempts to dissuade an immigrant from pursuing medical school, the discouragement is seen as a reflection on the counsellor rather than on the immigrant's aspirations. In other words, immigrants are inclined to interpret such discouragement as a deficiency of the counsellor, not themselves.

In contrast, generations of conditioning have led many African Americans to surrender to feelings of despair and perceive themselves as restricted solely by their race and its societal implications. Malcolm Gladwell has discussed this learned response to adversity, which he attributes to the weight of American heritage. While not every indigenous Black American shares this mindset, a significant portion have internalised this conditioning.

Recent data from a Pew Survey revealed that 76% of black Americans consider their black identity to be extremely or very important to their self-concept. Moreover, many harbour a predisposition to perceive themselves as being governed by external factors rather than having agency over their own destinies.

I have a niece who attends Stanford. She often faces inquiries from fellow students about her origins, assuming she hails from the West Indies or Ethiopia. These questions highlight their unfamiliarity with an indigenous Black American who navigates academia with the same self-assurance as an Igbo immigrant at Stanford. My niece's resilience and self-reliance reflect an absence of victimisation or an external locus of control. Despite being an "Old American" with ancestral ties dating back to colonial Virginia, she does not carry the weight typically associated with American heritage.

A discouraging word doesn’t cause my niece to collapse in agony and self-doubt; in this regard, Gladwell might mistake her for someone of West Indian descent.

The same goes for another family member who is currently a student at another prestigious Ivy League institution. During the past year, I had the opportunity to visit this family member at college. During my visit, I encountered approximately ten to twenty other black students. Remarkably, only one of them identified as a self-identified, unmixed indigenous Black American, and that individual happened to be my family member. Our American roots trace back to Jamestown, Virginia, dating back to the year 1621.

It seems that “old black Americans” are a vanishing species at the Ivy League these days.

Sadly, a significant portion of the indigenous Black American community has adopted a mindset deeply influenced by the historical and cultural context of America. In this framework, words of discouragement hold a devastating power, capable of crushing spirits and undermining one's sense of self. Unlike some black Americans, my family doesn't carry this heavy heritage. That's why my niece and her cousin often get mistaken for people from the Caribbean, Ethiopia, or mixed-race students at their fancy colleges. However, these superficial confusions hold little significance for my young relatives as they forge ahead in their pursuit of medical school and research fellowship opportunities. They know exactly who they are.

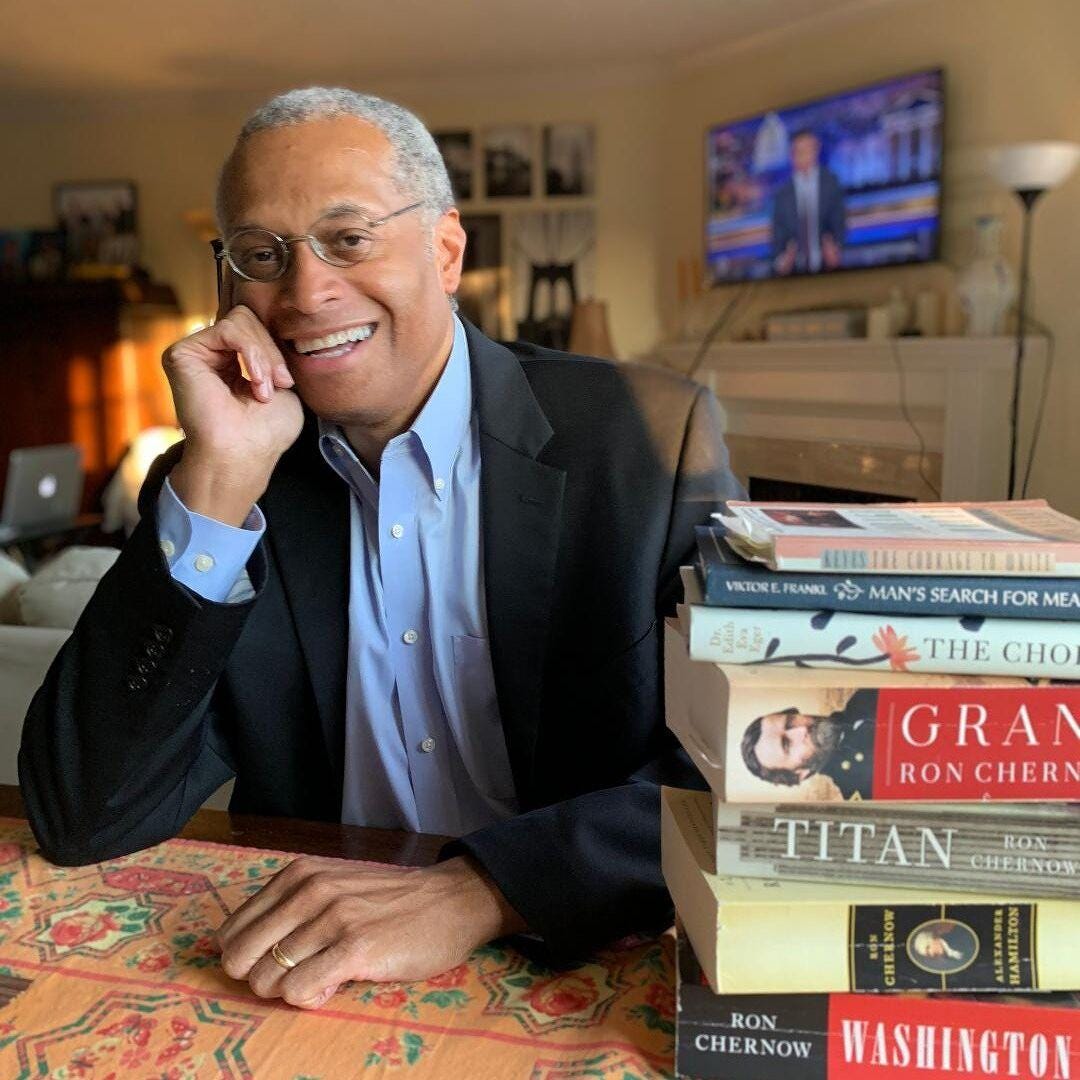

Winkfield Twyman, Jr. is the co-author of Letters in Black and White: A New Correspondence on Race in America. He is a writer, commentator, and former law professor. He has written for the Chicago Tribune, the San Diego Union Tribune, the Baltimore Sun, the Richmond Times Dispatch, and several other publications. He can be reached at twyman.substack.

Check out The Equiano Project YouTube channel for more great content. Search for Equianopod on Spotify, Apple and other podcast streaming platforms.