The Type of White Normativity that Activists Conveniently Ignore

Is the goal really to dismantle "white-centric" framing?

Originally published on Psychreg

An article headline in The Guardian earlier this year boldly proclaimed, "Women of Bangladeshi and Pakistani heritage earn almost a third less than white British men." This type of headline is common in reports on racial, gender, and economic disparities, and as I read the article, I couldn't help but notice two recurring patterns that appear frequently in such discussions.

Firstly, complex problems are often condensed into simplistic statistics, lacking the necessary context or impartial investigations into the underlying causes of these differences.

Secondly, it’s noteworthy that equality campaigners frequently critique "white normativity"—the dominance of white experiences as the societal default. However, when citing statistics about racial gaps, there seems to be no objection to the frequent comparison of minority groups solely to the white population. If the goal is to dismantle white-centric framing, why reinforce it through selective statistical comparisons?

The concept of white normativity generally refers to the normalisation and centering of white cultural values and norms. It is said to be evident across beauty standards, media representation, dress codes, and more. Another core facet of White Normativity is the practice of measuring non-white identities against whiteness as the presumed 'standard.'

However, race justice champions remain selectively unbothered by white normativity when spotlighting disparities in society, whether that's in education, health outcomes, earnings, and so on.

There seems to be a double standard, where white people are considered the default norm against which others are constantly judged. But again, this standard is only selectively applied when data portray whites advantageously compared to other so-called marginalised communities.

For instance, the underperformance and poor outcomes of white working-class boys, in comparison to ethnic minorities, are rarely emphasised using metrics and data. In fact, discussions about this subgroup of the white demographic are often dismissed as attempts to distract from or undermine efforts to address racial inequities. The focus seems to be on data that presents whites in a favourable way, while contradictory information exposing the difficulties of their disadvantaged subgroups is overlooked or dismissed as a tactic to demonise anti-racism initiatives.

Constantly framing conversations about disparities in terms of 'non-whites versus whites' is illogical if whites aren't the only group experiencing positive outcomes in society.

For instance, The Agenda Alliance, an organisation of 'bold, ambitious feminists,' reviewed data obtained from the UK Department of Education regarding school exclusion rates for the 2021/22 academic year. They noted that pupils from a black Caribbean background, especially girls, were excluded at twice the rate of white British girls from schools in England.

Yet again, it's intriguing that the comparison defaulted to white students. Why not consider other groups with even lower exclusion rates than Black Caribbean students, such as Black Africans or Asians? For instance, the DFE report showed that while 16 out of 10,000 Black Caribbean pupils faced exclusion, only 5 Black Africans did. The data for Chinese and Indian pupils was even more revealing, with only 1 out of every 10,000 experiencing exclusion.

So why do equality activists shy away from comparing minority groups to other minorities who have positive outcomes? Many fear that such comparisons obscure the role of racism when discussing collective outcomes. But perhaps the concern should not be proving racism to be an unconquerable and insurmountable force in society or trying to force racism into situations where it may not be relevant. We might make better progress by focusing on understanding additional root causes of social gaps, and yes, this does include exploring the seemingly forbidden territory of cultural patterns and habits.

This is not to minimise the fact that some people face unfair challenges in life, of course. But unfair disadvantages, whether natural or socially constructed, are not the only cause of unfavourable outcomes.

The path forward requires intentionally moving away from reductionist narratives that present racism, sexism, or any single force as a one-size-fits-all explanation for the disparities observed in society. This will provide a better understanding of group inequality and allow us to work towards meaningful solutions that address the multifaceted nature of social disadvantage.

We must also broaden the scope of comparison to include all groups and seriously consider the differences and inequalities found within ethnic minority groups. This warrants as much, if not more, attention than the inequalities between ethnic groups themselves. Only through such holistic approaches can we then tailor nuanced, context-specific solutions that uplift each individual and group, leaving no one behind.

Ada is the Head of Content at The Equiano Project. Subscribe to The Equiano Project YouTube channel HERE.

🚨Upcoming Events from The Equiano Project🚨

End of Race Politics with Coleman Hughes & Inaya Folarin Iman

Tickets available Here.

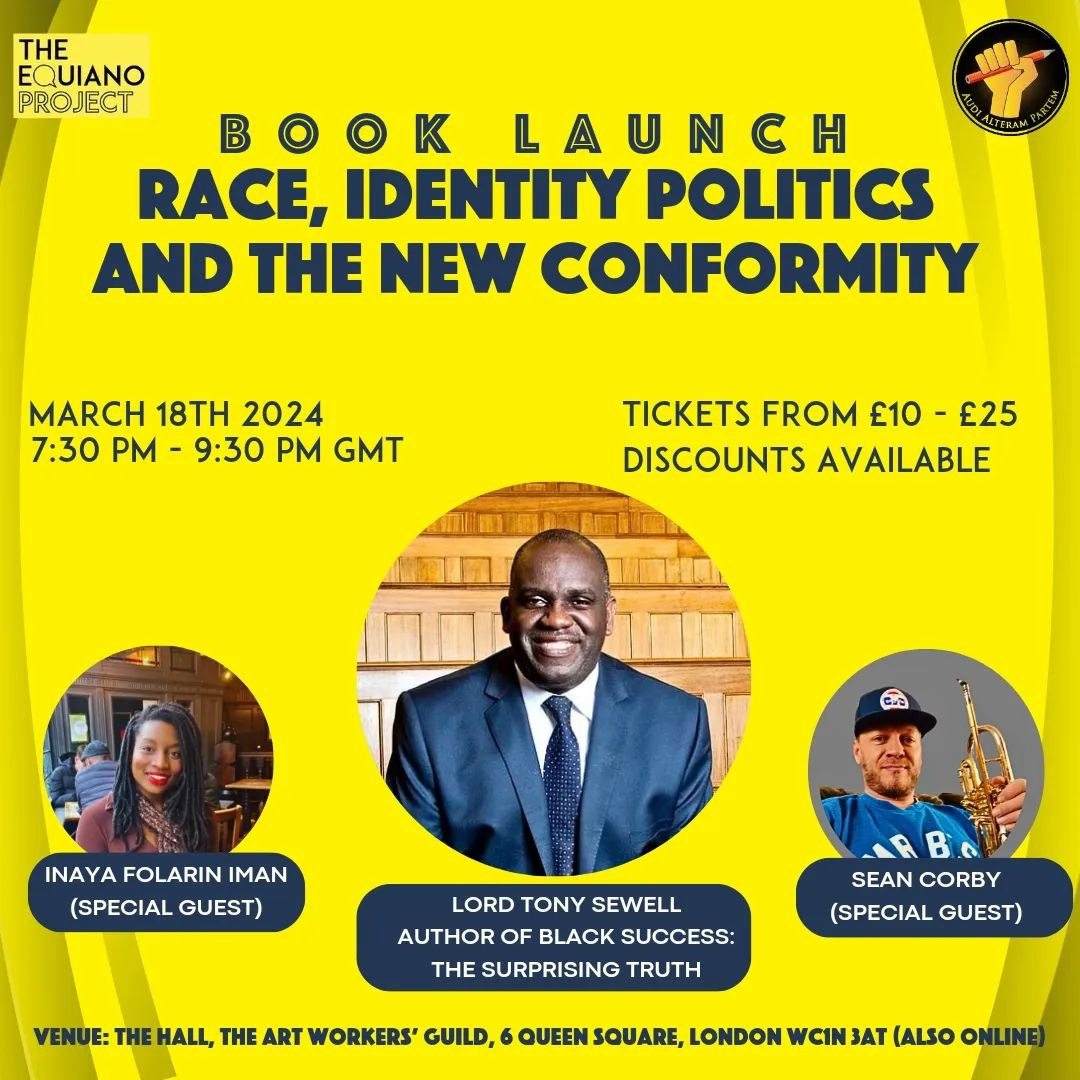

Race, Identity and The New Conformity

Tickets available Here.

Watch related content on our YouTube channel.

Brilliant piece. Thanks.

Great article. Thank you!