Graeme Kemp reviews ‘The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time’ by Yascha Mounk (2024)

Yascha Mounk’s book ‘The Identity Trap’ is a robust defence of liberal values in the face of a regressive identity politics that threatens to reverse progress on racial issues and trample on the liberal, democratic values that enabled that progress to be made.

These liberal values used to define the belief system of the political left. However, Mounk notes how the new ideology of identity politics is redefining the rules and norms of mainstream institutions in society - and the beliefs of those who describe themselves as ‘progressive’.

Much of this liberal emphasis has been lost over the past few decades.

“The left has historically been characterized by its universalist aspirations. To be on the left was to insist that human beings are not defined by their religion or their skin color … A key goal of politics was to create a world in which we collectively realize that the things we share across identity lines are more important than the things that divide us, allowing us to overcome the many forms of oppression that have marked the cruel history of humanity.” (Page 8).

From the 1960s and 1970s onwards, sections of the left started to argue that if prejudices existed against ethnic and minority groups in society, then new kinds of political activism and group pride were needed. If each racial group in society was to receive its fair and proportionate share of resources and jobs in a society, then both state and private institutions must deal differently with people, based around the identity group to which they belonged.

Mounk highlights that such thinking results in often jaw-dropping examples of new a kind of racial segregation, something that’s being introduced into society as an apparent way of dealing with racial inequalities.

Private institutions must deal differently with people, based around the identity group to which they belonged.

In Chicago, Evanston Township High School now offers separate calculus classes for pupils who identify as black.

In Rhode Island, a private school called Gordon divided children into racial affinity groups, even in kindergarten. The children were so young that many had to be told which racial affinity group to join. Disturbingly, this school offers a “play-based curriculum that explicitly affirms racial identity” (Page 2) according to Julie Parsons, a teacher at Gordon. Far from being condemned for such racialised thinking, the school has received praise from the National Association of Independent Schools (USA).

Elite institutions are often embracing divisive identity politics. And Mounk supplies more frightening examples of how bad things really are.

As the Omicron variant of the COVID virus surged a few years ago, doctors in the USA were faced with the need to decide how to allocate scarce resources. This led to medical thinking being influenced by racial equity values that aimed to address past racial discrimination, by paradoxically treating various ethnic groups differently.

Mounk explains about one state in the USA:

Earlier in 2021, when vaccines were first being rolled out, Vermont encouraged young, nonwhite patients without preexisting conditions to get shots before allowing otherwise identical white patients to do so. And even though its own models showed that such a course of action would likely result in a higher number of deaths, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) urged states to give essential workers access to the vaccine ahead of the elderly on grounds that older Americans are disproportionately white.” (Pages 6 and 7).

So, what label does Yascha Mounk use to describe such awful identity politics? He uses the term “identity synthesis” (page 9) to describe the broad range of intellectual ideas, traditions and concepts that commonly focus on identity categories such as race, religion and gender.

The phrase ‘identity synthesis’ is arguably a better label than what some other authors have suggested, such as ‘cultural socialism’ or ‘cultural Marxism’. As Mounk points out, ‘identity synthesis’ is a more neutral term.

However, ‘Identity synthesis’ is still an illiberal creed, a new orthodoxy that cannot tolerate heresy.

He notes that in the USA;

By the end of the 2010s, a constricting orthodoxy had descended – not just on famous institutions … but on countless schools, associations, and corporations all around the country. Anybody who offended the political sensibility of their peers was liable to be portrayed as a sexist, a racist, or a secret sympathizer with Donald Trump…anybody who was guilty of such political sins would pollute the purity of the community …” (Pade 116).

As Yascha Mounk points out: when dissent or discussion is repressed, extremists can get to impose their radical views on us all. Yet dissent and discussion are vital to keeping any organisation or group sane.

So, Yascha Mounk pushes back against the constraints of this identity synthesis and grapples with its flaws. He praises, by contrast, the value of a universal human experience as a valid alternative to such a divisive ideology that encourages hostility between ethnic identities - and towards dissenters.

dissent and discussion are vital to keeping any organisation or group sane.

Mounk therefore advocates a return to a liberal, colour-blind anti-racism and policies. There can still be racism today, but there are better ways of challenging it and creating a society fit for everyone.

And a more universalist approach will help us do this and build a better future – and we don’t need the ‘identity synthesis’ to do that. Identity politics can encourage any ethnic group to see other racial groups as competitors for resources and status, not fellow citizens.

As Mounk points out:

My own politics are based on the conviction that principles such as the political equality of all citizens, the ability to rule ourselves through democratic institutions, and the central role individual freedom should play in the world remain the best guide to building a better future – especially if we recognize that these ideals are yet to be fully realized.” (Page 239).

He therefore concludes with an impressive defence of political liberalism. Political equality means that the way any state treats its citizens should not depend on their ethnic identity. We must work towards a society where categories like race and gender matter less than they do now. This also means rejecting a culture of racial victimhood.

We can make progress and even claim the higher moral ground – this means being open and honest about our opposition to the identity synthesis and our support for liberal values. And there is usually a reasonable majority we can appeal to – people mostly want to treat others, including minority groups, with respect.

Free speech is important – employees in an organisation should be encouraged to respect the opinions of others; cancel culture must end.

Yascha Mounk’s excellent book ‘The Identity Trap’ is therefore a valuable, comprehensive and thoughtful resource. It is highly recommended for anyone interested in the ‘culture wars’ – and how to end them in favour of a genuinely free, equal democracy, based on liberal values that benefit everyone.

The Identity Trap is available to buy on Amazon.

Graeme Kemp is a former teacher and civil servant who currently lives in the Midlands. He is an English and Cultural Studies graduate of several universities in England and Scotland. He has also contributed book reviews to the Don't Divide Us website and 'Bournbrook' Magazine.

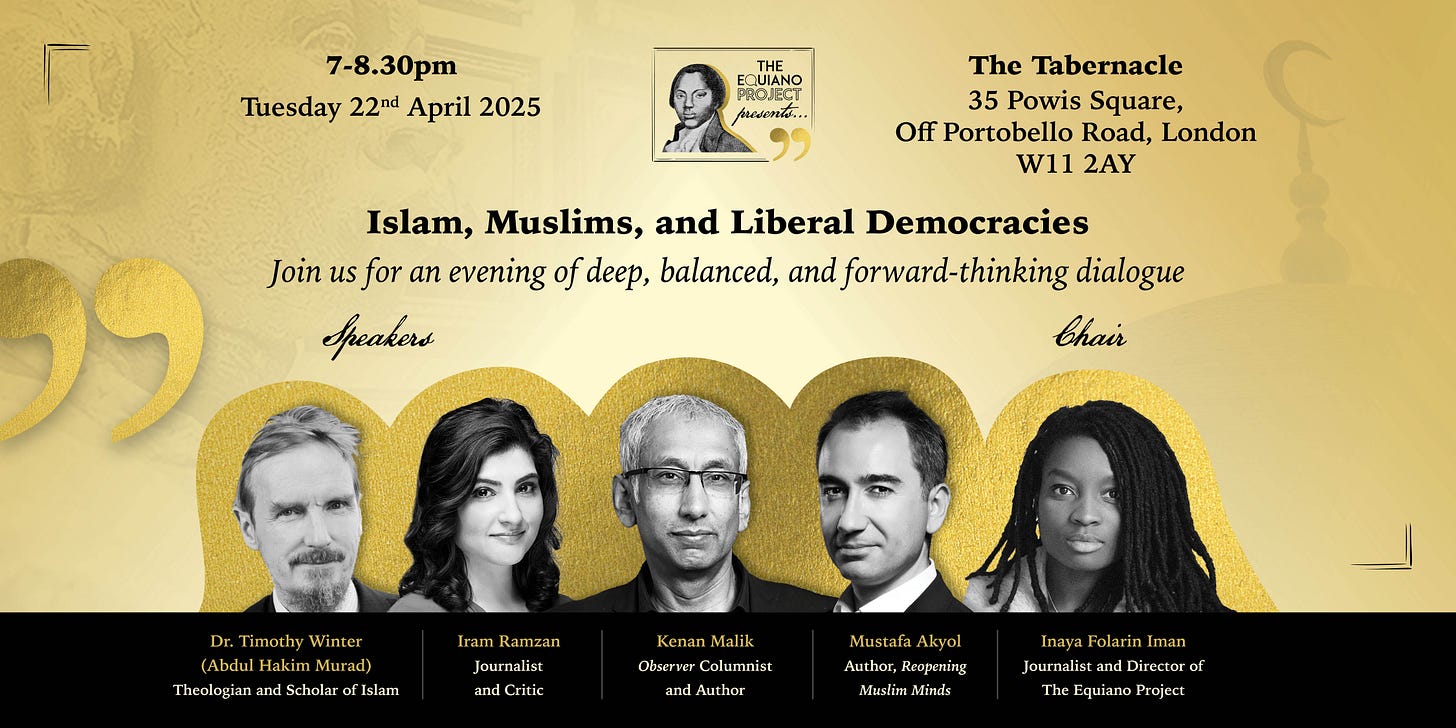

Don’t forget to get your tickets for our upcoming event, Islam, Muslims and Liberal Democracies, hosted by The Equiano Project on April 22nd. It’s a rare opportunity to have the kind of open, honest conversation that too often gets shut down elsewhere.

Click here to grab your tickets, or follow the link below.

(Paid subscribers are eligible for a discount—click here to redeem yours!)

Mounk seems to be a man after my own heart. Thanks for the review.