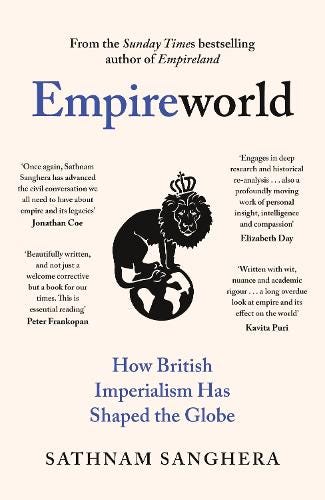

Empireworld by Sathnam Sanghera: Review by Vicki Robinson

Free speech is paramount in examining British imperialism.

Talking about the British empire is a free speech issue, something Sathnam Sanghera knows all too well. During his first ten years as a journalist, he received one racist email. All this changed in 2021 when he published Empireland, which examined how imperialism has shaped modern Britain. Sanghera found that “racist abuse ingrained itself into my existence, becoming as commonplace as my morning bowl of porridge.” These attacks, clearly an attempt to silence him, must be condemned.

Though apprehensive about tackling the subject again, a tour of a colonial plantation house in Barbados – which avoided the history of slavery, despite the guide wanting to focus on it – spurred him into action. Empireworld takes a broader perspective than its predecessor, Empireland, scrutinising British imperialism’s impact on the wider world and Britain’s place in it today.

Sanghera’s in-depth research took him around the globe. The bibliography and notes run to nearly 180 pages, and every topic he deals with is referenced meticulously. Useful Plants, his chapter exploring the British empire through the prism of botany, is fascinating and a great improvement on the “British gardening is racist” meme that spread on social media a few years ago. I will never see Kew Gardens in quite the same way again. His analysis of how tremendous innovation also led to tremendous environmental damage – and the birth of the environmental movement – gives an important moral lesson.

This approach runs through the book and forms its central idea. For Sanghera, the British empire was a paradox and an “incredibly complex mass of contradictions.” He is frustrated by the “balance sheet” approach to history, arguing strongly that “in geopolitics and in life, opposite things can be true at once.” A paragraph on democracy exemplifies his thinking:

“It’s true both that the British Empire sowed discord and chaos across the planet and that it gave birth to democracy in all sorts of places. The British Empire didn’t always sow discord, nor did it always plant the seeds of democracy. Similarly, democracy in former imperial states hasn’t always led to stability; instability hasn’t always stopped the subsequent development of democracy, and there are places like Nigeria and India where the British Empire can be credited/blamed for both the democracy and the instability.”

This concept of a paradoxical empire provides a useful framework for the ethical intricacies of imperialism and is, for me, the book’s greatest strength. In A Rational and Intelligible System of Law, for example, he explores how the law was not applied fairly to those under British rule – and used to challenge imperial corruption and abuses of power.

Sanghera does not shy away from the impact of the slavery, massacres and indentured labour instigated under British imperialism, and some passages detailing the violence that went unpunished are heartbreaking to read. He goes beyond description to look at the UK’s responsibility towards former colonies that are struggling to move forward, notably the twenty Caribbean countries represented by the CARICOM Reparations Commission. This is an important subject and one that the UK will have to discuss openly, given that the commission is reportedly seeking $19.6 trillion from Britain. Further debate is needed as to whether this is really the best way to help these countries.

British imperialism needs to be put into a wider context. Sanghera, for instance, writes movingly of the lasting impact of the British empire’s terrible exploitation of Indians, notably through indentured labour. But has the Hindu caste system – an ancient social hierarchy dating back thousands of years – not also played a role? What about the hierarchies of previous empires in the region, such as the Mughal? British imperialism did not wipe the world clean of all the cultures that came before it.

On occasion, Sanghera falls into the trap of seeing more positive views of the empire as the result of a colonial mindset. He uses a Times Radio interview with Kemi Badenoch as an example of Nigeria’s “intense imperial nostalgia.” Yet Badenoch was pointing out the dangers of a victim mentality and arguing for nuance: “There were terrible things that happened during the British Empire; there were other good things that happened, and we need to tell both sides of the story.” Sanghera’s mistake here is telling: his desire for balance only goes so far.

He could also turn his exemplary research to the antiracism movement, which has become increasingly censorious in recent years. Antagonistic generalisations such as “Britain is a racist country,” along with the demonisation of anyone who challenges the prevailing academic orthodoxy, have contributed to a fraught atmosphere around the subject of empire. Nigel Biggar, who also argues for nuance, has received a staggering amount of abuse since he challenged the Rhodes Must Fall movement in 2016. In 2017, 58 academics wrote an open letter calling for a boycott of his interdisciplinary Ethics and Empire course. Such attacks damage further conversation, wherever individuals stand in the debate.

Free speech is paramount in examining British imperialism. Diverse opinions must be heard, and Sanghera’s perspective is an important one. His ethical framework is helpful, as is his focus on the impact of empire on 21st century life across the globe. Empireworld makes an excellent starting point for such conversations. Its underlying themes could be developed by asking why some former colonies (such as Singapore and India) are thriving, while others are not. A range of approaches to bringing economic balance to the world could be considered. Throughout all discussions, it is important to remember that contemporary Britain and the wider world are much more than the period of British imperial rule.

Vicki is a writer from England's border with Wales. Her main interests are politics, arts and culture. She is also a keen amateur potter and sculptor.

You can follow Vicki on Twitter, @storiesopinions

More content on our YouTube channel. Don’t forget to Subscribe.