Can National Service Fix Britain’s Social Divide?

Restoring civic pride and social cohesion in a fragmented Britain

- Andrew Hamilton

Economic stagnation, a rapidly aging and diversifying population, turbulent European and global geopolitics, and a pervasive mental health crisis—the UK faces a torrent of complex challenges.

There is not a single fix to address this no-where-near exhaustive list of problems. However, one such initiative would go a long way towards transforming British society. It would help ensure citizens are aware not just of our rights, but also of our responsibilities to serve one another and the wider collective despite our national, ethnic, or religious differences. I’m referring to a policy concept sometimes dismissed as a relic, national service.

Let me elaborate first on a central plank of nationhood which is missing from British, and especially English, society. Civic nationalism is seemingly absent, and national pride is in steep decline for a variety of reasons. Without a strong backbone of civic nationalism, our social solidarity and cohesion, already damaged by our neoliberal economic framework, will degrade further, opening up our communities to unrest and amid further fragmentation.

This lack of solidarity and cohesion is potentially dangerous in a society that is rapidly ageing, and one that is following the salad bowl model of multiculturalism, rather than the melting-pot model. Ethnic minority groups are especially disenfranchised with the political and democratic process, and neglecting their frustrations and lack of belonging ensures trouble down the road.

In today’s neoliberal world most of us tend to feel that it is every person for themselves, that all of us exist in our own little bubbles and have little to do with anything or anyone else going on around us. Mrs Thatcher said that there’s no such thing as society, and it is this mindset that has permeated from Whitehall down to all levels of society, feeding the hyper-individualistic attitudes harboured by so many of us.

Against this bleak backdrop a fightback must be undertaken which builds a solid sense of social responsibility and citizenship that doesn’t centre around ethno-nationalism. How can we construct a cultural foundation that can help ground Britain's communities in an appreciation for democracy, Western ideals, and other communities?

Sometimes a system-wide shock is the best medicine. Liberalism, democracy, and individual freedom are the foundation stones of a just society. However, their survival sometimes necessitates policies that may appear illiberal. In times of extraordinary internal or external threats, temporary restraints, such as national service, may be essential to safeguard an open and just society. I am of course drawing inspiration from John Stuart Mill and his “Harm Principle” and “Considerations on representative government”.

National service could provide this system-wide shock. A shock which could reinvigorate our society’s broken social fabric, and bind communities and individuals together in a shared common cause.

Originally introduced in 1947, national service, which was basically a form of peacetime conscription, required all 17-21 year olds to serve 18 months in the armed forces. This was discontinued in 1957 due to a range of factors but mostly stemming from external influences, such as the Suez crisis and budgetary challenges. For many decades no movement or organised push to reinstate national service existed, despite public opinion being in favour of reintroducing it.

There was a brief moment when it was in the political spotlight once again, when Rishi Sunak chose to wheel it out on the campaign trail in an attempt to fortify his traditional Tory base. Yet this may have done the idea more harm than good, blacklisting it as a Tory policy gimmick, when in reality it should be viewed as a partial solution to youth isolation, and a lack of social cohesion, amongst many other issues plaguing our society.

This idea of bringing back national service could be seen as a response to the perception that liberal democracy is decadent and listless, in the face of threats from the East and the West, in the face of the death of Christianity, and in the face of the meaning crisis where a chunk of society cannot feel a sense of shared purpose. In Sweden it has been shown to increase social solidarity, and further engage with wider civil society organisations. The National Service programmes of Switzerland and Singapore have shown the potential of such programmes to improve community ties and reduce ethnic tensions.

To add some balance to this argument I will address two common critiques of national service reintroduction frankly.

Would it be expensive?

To be frank, probably. The Tory figures from the 2024 general election (which I sincerely doubt are accurate) state that setting up the system would cost £2.5 billion. It would almost definitely cost much more than this. But what price can we put on social cohesion, improving our society’s resilience, and helping establish a robust sense of civic nationalism?

Would forced participation produce genuine commitment to civic duty?

Naturally, young people would resist being forced into anything—I know I wouldn’t have been too happy being made to volunteer. However, by offering a range of options for engagement, from military involvement, to emergency services, to government and third sector volunteering, the concerns of participants could be partially abated as they join a service stream which matches their career and personal aims.

An important conversation would be for political leadership and parties to visualise what national service would look like. As Brexit has shown, voting for something without a coherent strategic vision is a recipe for chaos. National service can take a variety of forms, whether through a strictly military oriented framework like the systems in place in Taiwan or Sweden, or through a blended system like Austria’s which offers civil service placements for those not wishing to take on military roles. No one size fits all, and it is important that policy-makers recognise our unique demographics and national mentality would warrant a very bespoke approach to establishing a new national service system.

Like I mentioned previously, national service is not a magic solution, it would need to be introduced alongside a plethora of initiatives to start to rebuild our deflated and battered sense of shared citizenship. Strategies such as reinvigorating the tired PSHE curriculum and expanding its take-up in schools (given most schools do not offer this to students), to ensure our young people are taught about the importance of democracy, liberalism, and our Judeo-Christian inheritance, whether we believe in Christianity or not.

Ultimately, reintroducing national service could at least be a key tool for addressing our many challenges. By cultivating shared citizenship, and a sense of social solidarity, it could provide the solid foundation from which we can rebuild and strengthen our increasingly diverse society. In unstable times it is especially important to shift our thinking from fixating on our rights, and more to thinking about our responsibilities to one another. Like JFK said, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country”. A well-designed national service system would go some way towards promoting this more proactive mindset.

Andrew Hamilton is a London based consultant and aspiring writer. He is passionate about exploring the debates around culture, nationalism, conflict and the climate crisis

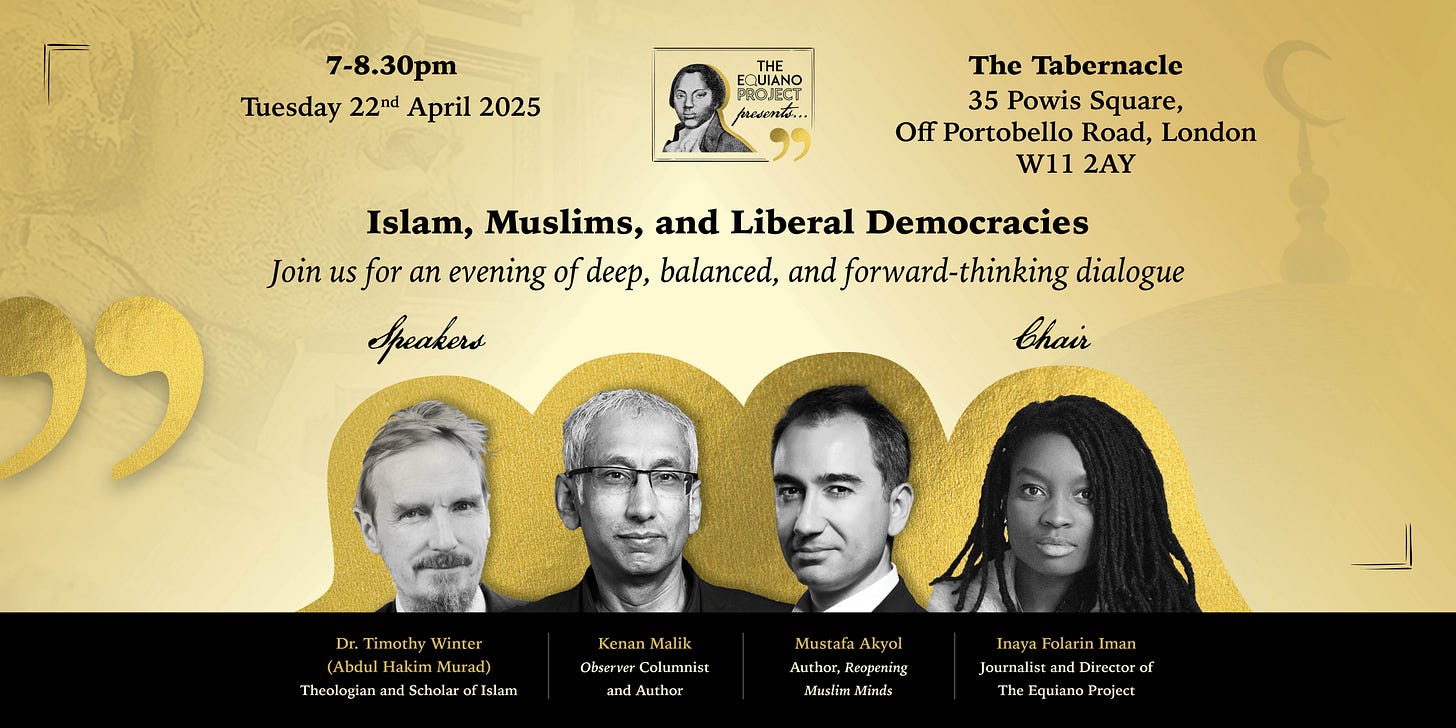

📢📢UPCOMING EVENT

Islam, Muslims and Liberal Democracies

An evening to discuss Islam’s place in Western secular societies

Click here to grab your tickets, or follow the link below.

(Paid subscribers are eligible for a discount—click here to redeem yours!)

I love the article and Andrew Hamilton makes a good case, a positive and optimistic case. The bigger challenges, in addition to introducing the scheme, would be the other 180° changes we would need to make in parallel. Persuading a teaching profession to do an about-face and start teaching the importance of democracy, liberalism, and our Judeo-Christian inheritance - well that will be a huge ask, totally against the grain. But I mustn't allow my natural cynicism and 'it'll never work' attitude to prevail. Instead, I'm grateful to people like Andrew who can see a positive future for our society and ways in which to make their positive vision become reality.

I'm really pleased the author mentioned Margaret Thatcher and her reputed comment about there being no such thing as society. It was Margaret Thatcher's policies that proved a retrograde step for Britain as far as I'm concerned.