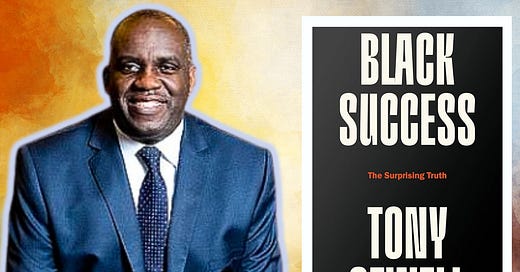

Black Success – The Surprising Truth (Book Review)

This story begins and ends with the powerful idea of agency.

- Written by John Root

At the time in early 1970s that Tony Sewell was attending an Anglican Sunday School in south-east London, I was leading a Pathfinder group of 60 or so of his mainly black contemporaries in north-west London. So reading his book at times generated nostalgia, often strong appreciation of his perceptions, and resonance with his positivity and love of reggae.

It is a book of two halves. Part 1 is ‘Education’, referring both to his own and his work as an educationalist. He describes his childhood and early education; his involvement in responding to life in Britain, especially writing regularly for The Voice newspaper; his work on The Hackney Learning Trust, overturning the shibboleths surrounding the education of black children; and setting up the Generating Genius project to develop STEM capabilities amongst black teenage boys.

Part 1 has already included capsules on what underlies ‘black success’, such as Jamaican sprinting gold medallists. Similar exemplary stories are the theme of Part 2 on ‘Black Success’ – he looks at Nigeria, not just the curious fact of it being world Scrabble champions, but also the role of faith. A chapter on the famous Jamaican nurse Mary Seacole imaginatively links her with the white Jamaican record producer, Chris Blackwell. Sewell flips the narrative of seeing her as a racialistically overlooked equivalent of Florence Nightingale to instead having the qualities that Sewell is foregrounding: readiness for adventure and the risk-taking utilisation of whatever resources life has presented us with. Instead ‘she is made fit for the needs of modern white guilt and black historic racial trauma’ (page 170). The chapter on ‘The Housing Lark’ shows how the racism of landlords led the early immigrants to buy their own houses, creating long-term financial benefit. The final chapter utilises once more his love of stories, of ‘Odysseus and the Five Talents’, and exemplified in the success of the 1976 West Indian cricket team. It also highlights his central role in the highly controversial Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities, and his late life move into developing a ‘wellness’ farm back to his Jamaican roots.

Some characteristics of the book.

Imagination.

Sewell was an enthusiastic English Literature scholar at the University of Essex. His book, as noticed above, abounds in love for stories and imaginative connections. Thus he connects the Jamaican folk-lore stories about the spider god Anansi with D H Lawrence’s observation in ‘The Rainbow’ about the gargoyles on Lincoln Cathedral: they are ‘both in and outside the system . . . Black success is part of the orthodoxy, but it is also slightly separate. It is mischievous, practical, satirical and defensive.’ (p 45). It is ‘a blend of the sacred and the profane, the grand and the irreverent’ (p 54). Sewell is not just making a clever connection between Anansi and the gargoyle here, it is a ‘figure’ that underlies the whole book (and also, in a different register, his report). Utilising a phrase of the poet Derek Walcott, he writes, ‘we did get shat on, but we were smart enough to use it as fertiliser for the imagination’ (p 234). Sewell’s attempt to speak positively of the ‘Caribbean experience’ in his report aroused derision. In his book, he can more subtly explicate how brutal historical experience can be transformed into material for a rich and resilient inner life.

Myth Breaking.

It is this ambiguous and elusive stance that gives Sewell the clarity to see all the myths that have accrued around multi-racialism, so the ‘conventional myths about black success need to be unpicked’ (p 26). He spells out three increasingly common ones in his educational policy: ‘it’s twice as hard’, when being told the world is stacked against you simply encourages despair; ‘the curriculum is too white’, when ‘I was able to get on in life precisely because …. I delved into the classics’; ‘you can’t be what you can’t see’, when it is the competency not the colour of teachers that matters (pp 37-39). The extraordinary and policy-changing success of The Hackney Learning Trust was based on their readiness to abandon these sorts of untested clichés.

Instead he came to realise that ‘When we focused on the main issues of good leadership, high expectations and subject knowledge, black children really succeeded. The idea that teachers needed lessons in unconscious bias training, or that black students needed sessions on how Egypt was a black kingdom, were nothing but big diversions (p 128). His iconoclastic approach runs through the book, as in his overturning of the BHM myths about Mary Seacole. At a time when discussion of race too often consists of black grievance rhetoric responded to by white soft-ball, Sewell cuts through the pieties of our time and rather puts confidence in his own experience and in objective evidence and outcomes.

Family and fathering.

Sewell quotes his ‘Voice’ colleague, Marcia Dixon’s assessment of what were ‘the upstream reasons why the Caribbean Community couldn't build on the success of the early Caribbean pioneers. This had everything to do with the collapse of the family’ (p 57). As regards his own extensive work with black boys as both a teacher and an administrator, he writes: ‘My sense is that African Caribbean boys did suffer a particular trauma. Because the male authority figures in their lives were problematic.... I think we would have gone further had there been political leaders willing to admit that we had a family crisis that needed professional support’ (p 88-89). My impression is that such an emphasis on the family and especially fathering as a determinative outcome appears more strongly in the book than in his Report.

While he celebrates the positivity that he received from the Windrush generation, notably his mother, his narrative also laments real decline: ‘What seems to have changed for my generation was the introduction of priority council housing, which incentivized single motherhood and spelled the end for reliable fatherhood. This, combined with mass unemployment, knocked the enterprise stuffing out of a generation. We never really recovered’ (p 204). Sadly, this fits with my own perceptions over the generations.

Wariness of ‘race hustlers’.

In this unsettled situation, Sewell also notes policies and people that can make it worse. ‘It was clear to me that emerging alongside a genuine struggle for racial justice were race hustlers. They needed - and still need - a narrative of victimhood in order to keep their jobs, receive grants, and stay relevant. Sadly, this hasn't changed – there are new books and films released seemingly weekly that revel in black misery’ (p 71). He refers to Steve Pope, his editor at the ‘Voice’ being dismissive of the intellectual pontificating of today's black identity politics, which he claims is a middle-class obsession’ (p 69). The outcome is the bureaucratisation of racial interaction. ‘I feel some concern that the burgeoning ‘diversity and inclusion’ sector, valued at around five billion pounds, is sucking up black talent’ (p 241) instead of productive technical skills.

Further white attitudes now collude with these negative developments. ‘This white guilt literature hangs like a weight on me every time I go back to Britain; these people never see the region as having its own agency. Once again, it's about them and how, in the end, they can have power of others. In this way, the guilty white liberal becomes guilty of a new kind of colonialism’ (p 225).

Christian Faith.

Possibly one ingredient in the acid that corrodes the delusions and deceit around policies on race is the prominence Sewell gives to Christian faith. He speaks very warmly of both the hospitable welcome and the seriousness of theology that he received at the Anglican church that his parents sent him to in Penge; thereby dispelling the myth that the church’s response to Caribbean immigrants was uniformly negative and racist. ‘The church opened my eyes, my mind, and my world’ (p 29). Concerning his time at the ‘Voice’ his warmest accolades are for Marcia Dixon’s outspoken and challenging Christian section, ‘Soul Stirrings’. We find positive encounters with Christian brothers such as Bishop Joe Aldred and Israel Olofinjana, all of Matthew 25:14-30 printed in full, and his book concludes by referring to my blog #113 on ‘Good Story, Bad Story + Lynne’s Story’.

It would be interesting if his essentially ethical understanding of the Christian faith was enriched by seeing the transformative power of God’s grace so that the one who has been ‘shat upon’ has, through faith, become the source of new life and hope.

Agency.

‘This story, this good story, begins and ends with the powerful idea of agency’ (p 242). Thus he began his introduction by describing his friendship with American Jamaican educationalist Ian Rowe, whose book on agency uses FREE as an acronym for Family, Religion, Education and Enterprise. So he tells the stories of those who found ‘For all its persistent racism, Britain was nevertheless a place of creativity, possibility and success’ (p 190). So he is unimpressed that Michael Holding used a space in a cricket commentary to lament a black history omission, when ‘I wanted to hear the story of how [the 1976 West Indian cricket] team came up in the world; of how organised, professional and scientific black people really are.. It is a world away from stereotypes around instinctive athleticism’ (p 220).

His own story recounts positives. Based on his mother’s frequent assertion that he was a ‘genius’ (though he failed his 11+), he experienced good outcomes - getting a plum job in his local library as a schoolboy—while his enthusiasm to discuss with his lecturers at university led on to social and life-long friendships with them. His apparent enjoyment of a fulfilling life might suggest that what a person expects from their society powerfully determines how they experience it

Tony Sewell’s Report made him enemies. (The Acknowledgements thank Adele and Zindzi ‘who knew that after the storm would come the calm’; but with no attribution to Desmond Dekker!). I guess this book, with its personal and analytical elements, will cause less of a storm, not least because of the pressure of evidence, but it still upsets apple-carts of myth and posture that will invite pushback. But hopefully it will be well read by politicians, educationalists, policymakers, and church leaders, and so shift us towards policies that respond more appropriately to the present realities of multi-ethnic Britain.

John Root is a retired Anglican clergyman, living in Tottenham. He has been vice-principal of a Cambridge theological college and was for thirty years vicar of an ethnically ’super-diverse’ church in Wembley. He has also lectured part-time in early colonial history. His wife is Indian, from Malaysia and they have an adult son. You can read more of his work here.

🚨Upcoming Events from The Equiano Project🚨

End of Race Politics with Coleman Hughes & Inaya Folarin Iman

Tickets available Here. (Free Tickets for our paid subscribers. Email ada@theequianoproject.com to receive your code.)

When Grandmaster Flash sang 'don't push me cause I'm close to the edge' in 1982, I was pretty close to the edge and subsequently went right over the edge. The early 1980's were a difficult time for black people in the UK, particularly for young black men. The political right under the Thatcher government were in the ascendancy and the extreme right were also on the rise. The issue of police harassment has been well documented, we also had serious mental health issues. Many of us were coming out of adolescence with raging hormones and as children of immigrants trying to find a sense of time and place.

I welcome Sewell's input, put we also need a space for alternative perspectives. I went to Warwick University in 1981, I joke that I wanted to escape the tensions of South London and ended up in Coventry just as Jerry Dammers and The Specials were putting the final touches to 'Ghost Town' about, erm Coventry.

I was looking for an outlet and I did notice that there was a group called 'Race Today', there must be a story around the demise of this group, but nothing replaced it, we have had a dark ages of 40 years for black politics ( before thankfully, the Equiano Project). Ambitious black politicians and activists gravitated towards the Labour Party, and these cliques have dominated black politics ever since.

Today's Conservative Party has elevated many black and Asian cabinet ministers, but none of them are from Caribbean backgrounds. Black Caribbean conservatives did not join the Conservative Party. In many respects Sewell is a Conservative figure, but he comes from a generation where for many black people (and white too) race has taken priority over class. So we have a coalition of the political left and paternalism, racial uplift, advocacy and state intervention (education, social work, psychology etc). So Sewell's laments about single parents and broken families can be easily co-opted into a Conservative worldview. Similarly the rise of black radical feminism in the 1990 could be and was co-opted as part of a critique of black men.

In the 1980's Conservatives were deeply concerned about the alienation and disruption of young black men, they began to think about producing a black middle class, again this agenda could be supported by black conservatives (albeit to be found on the fringes of the political left).

The 1980's saw the demise of the white working class, not so often remarked on was the demise of the black (predominantly male) working class, no longer agents in their own right, but subject to the interventions of middle class advocates berating them for their lack of success, and their poor choices.

Sounds like a solid read