A New Tribe of Us: Our Mississippi, Today

A story of love, race, and belonging in the Deep South

- By Adam Gussow

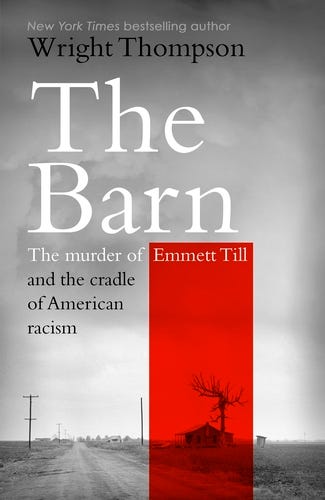

By now, many readers have heard of Wright Thompson’s New York Times bestseller, The Barn: The Murder of Emmett Till and the Cradle of American Racism. A deeply researched, ethically impeccable, and emotionally wrenching retelling of the infamous 1955 torture and murder of a Black Chicago teen in rural Mississippi. The book is epic in scope and deserves every award it is sure to win. I say this not just as Thompson’s fellow Mississippian—a relocatee from New York twenty-two years ago with a Mississippi-born son and a Texas-born wife—but as a scholar of the blues and southern violence who knows a fair bit about the deeply shadowed terrain Thompson is working.

Still, there’s a problem. The bad old Mississippi that Thompson evokes with such power and historical breadth, the slave-ganged linchpin of the Cotton Kingdom and brutally Jim Crowed, white supremacist fiefdom of James Vardaman and Theodore Bilbo, isn’t my Mississippi. Isn’t our Mississippi, I should say. The “busted place,” as Thompson termed his native state in a recent podcast with Chris Hayes, a state wrestling endlessly and tragically with its own ghosts, isn’t the surprisingly warm, welcoming, and supportive world in which my family and I have pursued our happiness, unhindered: a white man, a black woman, and our son.

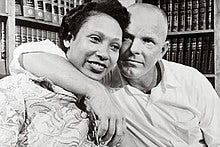

The interracial family circle I write about in my forthcoming memoir, My Family and I, shouldn’t exist—at least not if one reads The Barn carefully, searching for signs of white and black Mississippians, past and present, who not only fornicate furtively but also marry and raise their children openly, unburdened by communal condemnation.

Yet we do exist, my family and I. And we are the fulfillment of a prophecy that Thompson himself offers near the end of The Barn and reiterates during his conversation with Hayes. “The only hope it really has of surviving,” he insists of his native state, “is if there’s some sort of new tribe of us, where everyone and all of their stories are included. And we’re not even close to that.”

You’re wrong, Wright. That brave new Mississippi has arrived. Sherrie, Shaun, and I are that new tribe of us. Like our lives here in Oxford—which is your Oxford, too—our stories have been intertwined for a long time.

The term “the Ole Miss family” is thrown around promiscuously by coaches, administrators, and alumni alike, but the term seems to have been created with us in mind, although of course it wasn’t. It was created to banish all thoughts of the deadly riot that ensued in 1962 when James Meredith, with the help of his “Kennedy coon keepers,” registered for classes at the University of Mississippi. Yet here we are: your modern black-and-white Ole Miss family. Mom is an administrator in the Department of Biomolecular Sciences, Dad teaches English and Southern Studies, and Shaun, now 18, is a freshman music performance major who plays trombone in the Pride of the South marching band. We love the Grove, and our Rebs!

We’re fully invested in contemporary Mississippi. In other words, our mantra—if we had one—would be Myrlie Evers-Williams’s wise words, which Thompson invokes near the end of The Barn as he sits brooding in the same courtroom in Sumner, Mississippi, where Emmett Till’s murderers were found not guilty by an all-white jury. “Yes,” he drones, his eyes tearing up, “Mississippi was, but Mississippi is. The state deserves a chance to break free from its history.”

My family and I agree. We’ve been living that is for the past twenty years. We were initially unsure about how things would work out. The Mississippi mythology carries weight and breeds apprehension, even in the present-minded. “The past isn’t dead,” Faulkner famously insisted of his native state. “It isn’t even past.”

We whistled in the dark for a couple of years, waiting for the white supremacist race-police to show up and go Boo! Race mixing bad! But they never did. So we had a kid, back in 2006. And the rest is history—our history, the past we have made together out of love, hope, and the slow patient accumulation of daily life.

In 1957, the year before Richard and Mildred Loving married and a full decade before the US Supreme Court declared so-called “anti-miscegenation” statutes unconstitutional in Loving v Virginia, Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke about his dream of beloved community, urging us toward an “America where brotherhood is a reality....Our ultimate goal is genuine intergroup and interpersonal living—integration.”

When you share space as my family and I do in our cozy three-bedroom house at the foot of a curving suburban drive—not just space, but bathroom scent, hair brushes, dishwashing duties, holiday portraits, pots of homemade gumbo, and the TV remote—integration is a given and the bugaboo of race fades away, unneeded.

Sherrie and I chatter excitedly as we kick back in front of the living room TV and kibitz about boxing matches and The Voice. She’s made me a fan of the Dallas Cowboys, thanks to her weekly fall-and-winter fix, and I’ve made her a fan of the New York Marathon live broadcast. We both love the bittersweet piano jazz of Vince Guaraldi during the holidays, since we grew up on A Charlie Brown Christmas. This December, home for a few weeks from his campus dorm room, Shaun brought his keyboard into the living room to play “Christmastime Is Here,” a song he taught himself from sheet music after honing his skills in a freshman piano class.

There are few marital satisfactions more profound than raising a musically gifted son capable of gifting the family circle with its treasured soundtrack. Beloved community begins at home. But it broadens and deepens when we cross the threshold. And Oxford, Mississippi, of all places, has been a uniquely supportive space for a family like ours.

The schools, for example. Unlike the Delta, where white flight to segregation academies in the early 1970s rendered the public schools all-black and chronically underfunded, Oxford—chastened by the riot of 1962 and determined to serve both faculty children and the town as a whole—got things right. According to the most recent data, the Oxford School District student cohort is roughly 50% white, 35% black, and 15% everything else, including a 5% tranche of mixed kids like Shaun. Prom nights in our Mississippi town are unified, not segregated. Hard as it may be for skeptical blue-state folk to believe, Oxford, Mississippi has some of the most thoroughly and peacefully integrated public schools in America—not just the students (including athletic teams), but teachers, administrators, and peace officers.

This sense of genuine intergroup and interpersonal living that King spoke of was there in the Mississippi Shaun encountered as a boy and grew into as a young man—a world that stands at an infinite remove from the violently white supremacist Mississippi hellscape that lynched Emmett Till in 1955. It was there in the taekwondo ministry of Master Ra’s gym down on University Avenue, where Korean-born Ole Miss graduate Sung Ra, class of 2004, has schooled class after class of local kids not just in high-flying kicks and blocks, but in the five tenets of TKD: courtesy, integrity, perseverance, self-control, and indomitable spirit. (Aniah Echols, one of Shaun’s Team Ra peers, appeared on Good Morning America after becoming the first middle school girl to play on the boys’ football team at Oxford Middle School.)

King’s dream was there, too, in the Mississippi band camps Shaun attended over the years. It was a wild menagerie of sounds and scales and the greeting of last summer’s friends on audition day. All of it was driven by a palpable faith that every kid would be judged by the content of his or her musical character—i.e., skill level—before being sorted into a half-dozen color-coded bands, from Red down through Bronze. Shaun thrived in this pop-up community of quirky, competitive young musicians and their stewards: a beloved community, after a fashion, charged with the mission of getting it together and putting on a good show. King might have called it an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.

Yes, Mississippi was. But Mississippi is. And that’s where we live. Thank you, James Meredith, for opening up a space in which we and our son might thrive: an Ole Miss family, proud to be Rebels.

Adam Gussow is a professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. His latest book, My Family and I: A Mississippi Memoir, will be published by Emancipation Books in February 2025.

Such a lovely, uplifting, optimistic article. Thank you!

“My Mama always said you've got to put the past behind you before you can move on” is a quote from the 1994 movie Forrest Gump. Thanks for moving on and sharing the beauty of a new Mississippi.